Stuart Forster experiences one of the top things to do in Charleston for military history lovers by taking a boat trip to visit Fort Sumter, the site of the first battle of the American Civil War.

Disclosure: Some of the links below and banners are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

It’s a bright and mild spring morning in Charleston, South Carolina, as I walk towards the Spirit of the Lowcountry near the Aquarium Wharf. Docked at Liberty Square, the 93-foot vessel looks much like one of the paddle steamers that sailed in Charleston Harbor more than a century ago. But her appearance is deceiving. She is one of the largest hybrid-powered passenger ships in the United States of America.

As I step aboard, it strikes me that this would not be a part of the USA had the Confederate States of America triumphed in the Civil War that was fought from 1861 to 1865. On 20 December 1860, South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union. The boat that I’m on is about to sail to Fort Sumter, the site of the first battle of the American Civil War.

Military history in Charleston

Across the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge, on the far side of the Cooper River, the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown is docked next to other historic warships. The floating exhibits draw visitors to Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum.

There’s much to do in and around Charleston for military history aficionados. Significant action was witnessed in the area during the American Revolutionary War, fought from 1775 to 1783. Fort Sumter was named after one of the heroes of that conflict, General Thomas Sumter.

The Hunley, the first submarine to sink an enemy ship in action, is displayed at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center. Shortly after sinking the USS Housatonic in February 1864, the Confederate vessel disappeared and was not rediscovered until 1995.

Today I’m heading out to Fort Sumter National Monument to learn more about the events which sparked the American Civil War and to visit the site of its first battle.

Sailing in Charleston Harbor

As we pull away from the dock, it’s hard to imagine Charleston Harbor as a battle site. There’s a gentle breeze and the blue water is placid. Pelicans fly low over the surface of water that dolphins weave through in the near distance. Over the starboard side, I gaze at the elegant pastel-coloured façades of Charlestonian houses and the tall, tapering spires of the city’s churches.

Shortly after departure, we cruise past the tiny Shutes Folly Island: the location of Castle Pickney. The horseshoe-shaped fort was constructed in the first decade of the 19th century to improve the defences of Charleston Harbor. Named after George Washington’s ambassador to France, the fort is now owned by the Sons of Confederate Veterans. That group is permitted to fly a flag above the fort and today the French tricolour is fluttering.

The South Carolina Militia captured Castle Pickney on 27 December 1860. For a time, Union prisoners of war captured at the Battle of Manasses of July 1861, also known as the First Battle of Bull Run, were imprisoned at Castle Pickney.

On the 30-minute journey out to Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historic Park, a uniformed member of the National Parks Service outlines the history of the place that we’re about to visit. She explains that 70,000 tons of rock and granite were imported from New England to create an artificial island for the fort.

The stronghold was one of many planned and built to protect the borders of the USA following the War of 1812 against Great Britain, the 19th century’s naval superpower. Fort Alcatraz, in San Francisco Bay, was the most westerly of the forts.

Slavery and Fort SumterAs many as seven million bricks were used in constructing Fort Sumter. They were made on plantations by enslaved people.

Slave labour was also used to build the fort from 1829 onwards.

Those are not the national monument’s only connections with slavery. Although the USA outlawed the transatlantic slave trade in 1808, in 1858 the US Navy intercepted a slave trader and brought its human cargo to the still unfinished Fort Sumter.

The issue of slavery was at the centre of political tensions in the US ahead of the 1860 presidential election of November 1860. The victory of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate, was a catalyst for things to further escalate.

Civil War approaches

Tension was spiralling towards hostility in December 1860. On the night of 26 December 1860, six days after South Carolina seceded, Major Robert Anderson moved his Union troops from Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island to the more easily defendable Fort Sumter. That was viewed as an act of aggression.

The Confederacy was formed in February 1861. By then it was clear to Major Anderson that, unless resupplied, Fort Sumter’s provisions would not stretch beyond mid-April and he would have to evacuate his troops.

He came under pressure to depart sooner. Eventually, Brigadier General Pierre Gustave Toutant-Beauregard, a former student of Anderson at West Point, oversaw the attack that began at 4.30 am on 12 April 1861.

The first shot detonated above Fort Sumter. Though its construction was still not finished when the first artillery barrage of the Civil War began, the fort’s walls then stood as high as the flagpole that can now be seen in the middle of the fort. Following the initial signal shot, three batteries subsequently shelled Fort Sumter for 34 hours.

The fall of Fort Sumter

Eventually, heated shot, known as hot shot, caused a fire in the officers’ quarters. The garrison could not mount a defence while putting out the fire at the same time. Consequently, Major Anderson could take what was considered an honourable evacuation after his garrison mounted a valiant defence.

Beauregard agreed to Anderson’s terms. That included giving the Union garrison a 100-gun salute. Unfortunately, the 47th shot caused an accident which inflicted the first fatality of a war – Daniel Hough, an Irish immigrant serving in the United States Army. The conflict would see the deaths of over 700,000 soldiers and many more maimed and injured.

The surviving defenders of Fort Sumter were taken by ship to New York City, where they were greeted as heroes.

Fort Sumter National Monument

As the Spirit of the Lowcountry docks at Fort Sumter’s jetty, I look at the low brick walls of the fortification. A grey concrete blockhouse juts above the brickwork – it was added in 1898, in part because of rising tensions between the USA and Spain.

I stroll past a sign bearing the National Parks Service logo. It welcomes visitors to Fort Sumter National Monument.

Entering the historic fortification, my eye is drawn to the cannons sheltered in garage-like casemates on the ground level.

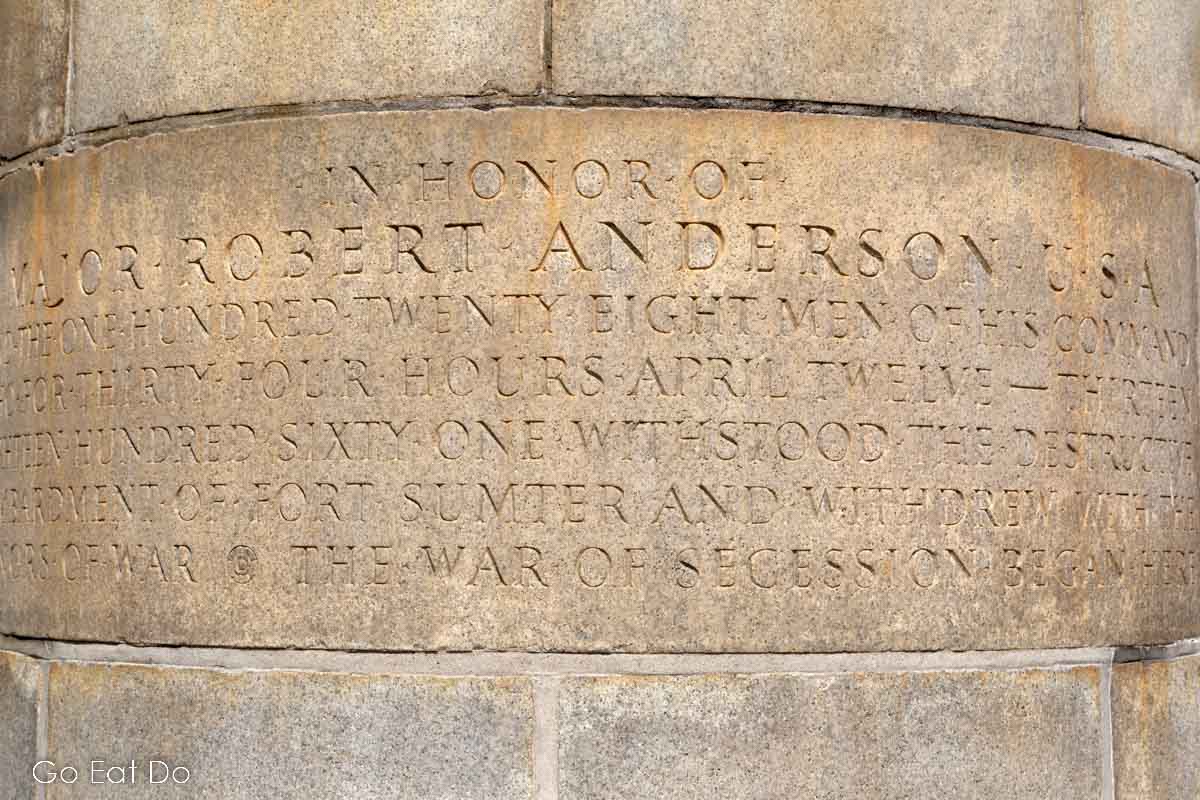

A stone monument honouring Major Anderson and his 128-strong garrison stands in the centre of the fort. In capital letters, the inscription summarises the historic events which took place here on 12 and 13 April 1861. To my surprise, it names the conflict that was sparked not as the American Civil War but as the War of Secession.

Fort Sumter flag raising

Shortly after I arrive, two men in uniforms announce that they are about to raise the flag and ask for volunteers to participate. One of them, Andy Solgere of the National Parks Service, makes a powerful speech which prompts applause and nods of admiration from onlookers.

“A lot of American citizens ask, ‘why don’t we play the bugle when we play the national anthem, or say the Pledge of Allegiance?’ and I say it’s because we want to be inclusive,” says Andy.

“We don’t want you to feel like you’re intruding on somebody else’s ceremony. And it’s not a ceremony, it’s a programme; we’re talking about history,” he adds.

“People died here for their beliefs. And whether any of us share those beliefs or not is irrelevant. It’s a battlefield. And we should think about that, and we should think about what that sacrifice represents. And, I think we can all come to the conclusion that if we remember, these types of really bad things, then hopefully, we won’t repeat them,” he continues.

Fort Sumter in the Civil War

Andy explains that during the last 18 months of the Civil War, the US Army occupied nearby Morris Island. From there 44,000 cannon projectiles were fired at Fort Sumter. Around 32,000 hit their target.

He points to locations around the fort where shells are stuck in the walls. As we watch, a visitor runs her fingers over the back of a metallic projectile embedded in the brickwork.

“The last person that touched the front was the US Army soldier who loaded it into a cannon over there during the Civil War, probably in September of 1863,” says Andy.

He points out an arched doorway. It was the entrance to the powder magazine and during the Confederate occupation, that exploded. As a result, the doorframe leans.

The wall next to the door is made of concrete derived from oyster shells. Slaves constructed the wall during the war to help protect the Confederate soldiers who were fighting the United States.

Andy explains that Fort Sumter was designed for 135 guns. Fort Moultrie, on the other side of the 1,200-foot wide channel also had dozens of guns. Together their artillery helped ensure that the main shipping channel into Charleston was impassable for enemy vessels.

The guns of Fort Sumter

When Major Anderson arrived at Fort Sumter the fort had 90 cannons. Between a dozen and 15 were mounted and ready to fire at the main ship channels.

“Anderson had his soldiers start moving the guns around. And the way you move these is kind of complicated…They started moving those guns to aim at Fort Moultrie, to aim at Fort Johnson right over the sandbar and to aim at Morris Island – over there – because all of those are within cannon range,” explains Andy.

The Confederate States of America wanted the Union Army out of Fort Sumter because of its importance to the defence of Charleston Harbor.

“Almost 100 per cent of the hard currency potential for the Confederate States was rice and cotton out of the Port of Charleston with winds fair for Great Britain that way and British colonies in the Caribbean that way,” says Andy pointing into the distance. “So they could not economically afford to stop trade…so that’s why the shooting started.”

Victory ceremony at Fort Sumter

For the last two months of the Civil War, Fort Sumter was under Union control.

Plans were made for an elaborate victory ceremony on the 14th of April 1865 at Fort Sumter. Major General Anderson (retired) returned and raised the US flag that is displayed within Fort Sumter’s museum.

On that same day, President Lincoln choose to go to Ford’s Theater in Washington D.C. to attend My American Cousin, a play written by Bishopwearmouth-born Tom Taylor. Lincoln was shot at the theatre and later died, meaning that the victory ceremony is largely forgotten.

After talking with Andy I head into the museum to view the Fort Sumter flag and other artefacts. There’s certainly plenty to think about on the boat journey back to Charleston.

How to visit Fort Sumter

See the Fort Sumter Tours website for information on how to visit Fort Sumter.

Map of Charleston Harbor

Zoom into the Google Map of Charleston and the surrounding area to see Fort Sumter and other locations in greater detail:

Travel to Charleston

Charleston International Airport is approximately 12 miles northeast of Downtown Charleston.

Books about Fort Sumter and the American Civil War

Keen to know more about Fort Sumter and the American Civil War? You can buy the following books from Amazon by clicking on the links or cover photos:

The Battle of Fort Sumter: A Captivating Guide to the First Battle of the American Civil War (Battles of the Civil War):

Thunder in the Harbor: Fort Sumter and the Civil War by Richard W. Hatcher:

The Cannons Roar: Fort Sumter and the Start of the Civil War―An Oral History by Bruce Chadwick:

The American Civil War: A Military History by John Keegan:

Browsing the Gift Shop

America’s National Parks Museum Store is located in the Fort Sumter Visitor and Education Center at Liberty Square and at Fort Sumter. Unique Souvenirs will engage the history buff and souvenir seeker alike. Books, CDs & DVDS include fascinating titles about Fort Sumter and the Civil War.

Further information

Head to the Explore Charleston website for further ideas about things to do in Charleston, South Carolina.

Learn more about things to do in the Palmetto State on the Discover South Carolina website.

Stuart Forster, the author of this post, is an award-winning travel writer based in North East England. He has written for publications including Discover Britain, The Telegraph and Wanderlust. He was named Travel Writer of the Decade at the 2020 Netherlands Press Awards.

Thanks for visiting Go Eat Do and reading this post about visiting Fort Sumter in Charleston, SC. If you are looking for a place to eat in Charleston, you may be interested in reading this post about Millers All Day.

Photos illustrating this post are by Why Eye Photography.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.

If you enjoyed this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts on a monthly basis.

Andy Solgere

March 6, 2023 at 02:44Thanks, Stuart. I’m glad you had the chance to visit Fort Sumter.

Andy Solgere

Park Ranger

Ft Sumter & Ft Moultrie Nat’l Historical Park

Go Eat Do

March 26, 2023 at 17:01Thank you, Andy, it really was a fascinating place to visit and one of the highlights of my trip to Charleston. The insights provided by you and your colleagues were very much part of that.