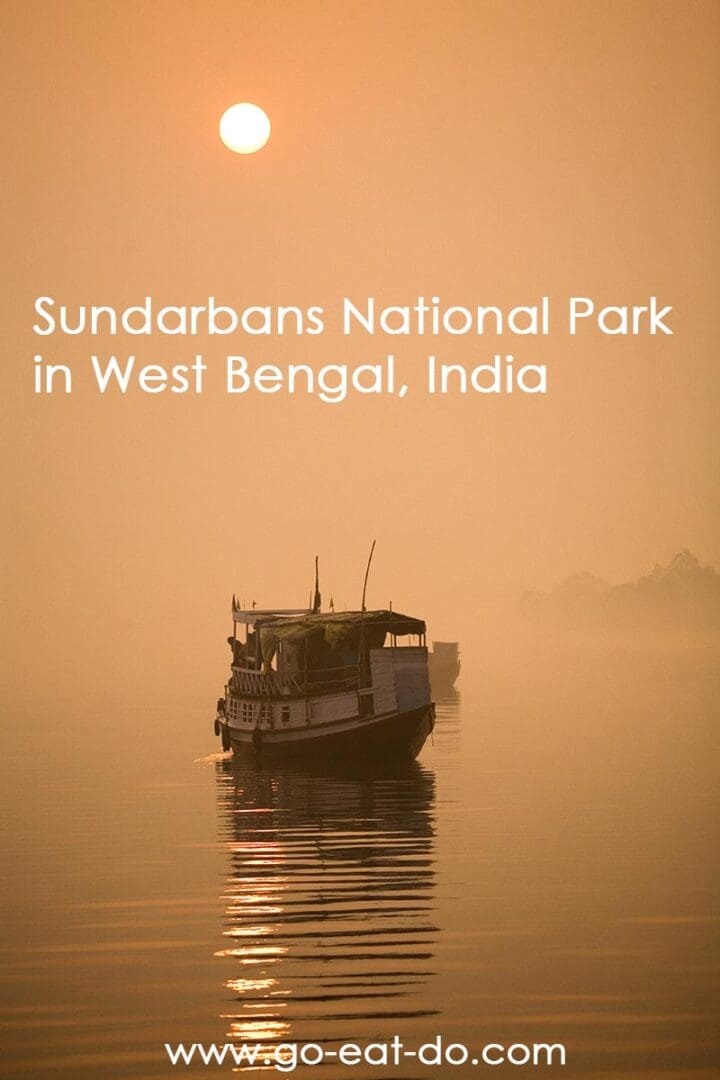

Stuart Forster visits Sundarbans National Park in West Bengal, India to view wildlife, understand conservation efforts and discover the significance of mangrove forest to the regional environment.

Disclosure: Some of the links below and banners are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Many of us tend to think of efforts to conserve the world’s natural resources as a fairly recent trend. In fact, the mangrove forest of the Sundarbans region has been a reserved area since 1875. Yet it’s only in recent years that researchers have identified the significance of the mangroves to the general well-being of West Bengal and neighbouring Bangladesh.

The Sundarbans is a series of islands and network of rivers. They stretch across a 354-kilometre (220-mile) wide delta of tidal waterways and saline mudflats, between the Ganges and Brahmaputra rivers along the India-Bangladesh border.

Ten per cent of the world’s tropical cyclones occur towards the north of the Bay of Bengal. Experts warn that the mangroves of the Sundarbans are a protective natural buffer against the destructive extremes of cyclones. The mangroves grow to heights of between 1.8 and 3.6 metres. They absorb some of the tropical storms’ raging power, thus protecting people and settlements further inland.

Mangroves for environmental protection

The protection that nature provides for free would prove dear to replace. The United Nations Development Programme estimated that $294m would have to be invested to build the 2,200 kilometres (1,367 miles) of flood and storm embankments required if man-made barriers were to provide the same level of protection as the mangroves. And the upkeep of the man-made barriers would come with an annual maintenance bill in the region of $6m.

Worryingly, some experts predict a 45-centimetre (nearly 18 inches) rise in global sea levels by the end of the 21st century. That could result in the destruction of almost three-quarters of the Sundarbans’ mangroves and also have a major impact on the region’s ecosystems.

Rising sea levels and population growth

The resultant rise in salt levels and the acidification of soil, the flooding of the Ganges delta and changes to the water table are also predicted to have major effects on the region’s human population and their quality of life. At present this process is being accelerated by natural subsidence in the Sundarbans, due to seasonal flooding washing away topsoil, which is causing the equivalent of a sea-level rise of approximately 2.2 millimetres (0.087 inches) per year.

Environmentalists point out that this is not the only risk to the area’s long-term security. The salinity of the Sundarbans is increasing. Experts know this process as salinization. When asked about the root cause of the issue, some experts point a finger in the direction of the Farraka Barrage, which, since 1974, has been diverting the upstream freshwater inflow of the Ganges with the aim of alleviating silting in the Port of Kolkata. This accounts for a 40 per cent decrease in the flow of fresh water during the dry season.

Conservation of mangrove forests

Rather than waiting until it’s too late, and the mangroves are lost, conservationists and a number of Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), such as the Mangrove Action Project, are working to raise awareness of the importance of conserving the remaining mangrove forests in protected areas.

They advocate environmentally aware tourism and environmentally aware acts, including the re-planting of carefully selected mangrove species along freshwater sections of reclaimed land, a technique that has already been successfully tested on Sagar Island.

Future of the Sundarbans

Without such steps – and environmentally aware decisions when infrastructure and development projects are planned – environmentalists fear that there may be very little left of the Sundarbans for tourists three generations from now.

That, they warn, would represent a significant loss, not only for India but for the world. The Sundarbans is one of just 213 natural sites on UNESCO’s list of 1,121 world heritage sites

Wildlife in Sundarbans National Park

The Sunderbans National Park has an area of 2,585 square kilometres (998 square miles), of which 1,330 (514) fall within a core protected area. Increasing numbers of tourists are becoming aware of the Sundarbans’ attractions – such as the region’s diverse wildlife, its complex ecosystems and the stunning natural scenery – thanks to cruises offered by West Bengal Tourism.

Tours are run on ships such as the M.V. Chitrarekha, pausing at sites of interest, nature camps and the Mangrove Interpretation Centre at Sajnekhali, where visitors have opportunities to learn about the 260 species of birds, 42 species of mammals, 35 different reptiles and eight species of amphibians which live here.

Crocodiles, monitor lizards and dolphins

Many people are surprised to learn that the Sundarbans hosts the largest estuarine crocodiles in the world, as well as monitor lizards, olive ridley turtles and rare Irrawaddy dolphins.

Nonetheless, most visitors come hoping to spot one of the region’s famous tiger population, the scourge of the wild honey collectors, known as mouli, who enter the forest wearing masks on the back of their heads to minimise the risk of attack by the big cats; they believe that if the tiger thinks it is being watched then it is less likely to strike.

Sundarbans Tiger Reserve

While the plight of the world’s tiger population gains significant column space in the world’s press, it is only recently that awareness of the threats to the Sundarbans has started to gain resonance. Some people believe that the region was named after the mangrove species which botanists know as Heritiera fomes, known locally as sundhari. Others argue the name is derived from the region’s natural beauty; in Bengali sundar means “beautiful” and bans translates as “jungle”.

Hopefully, decisive action will ensure much of the area currently inhabited by mangroves will survive and that the region continues to benefit from the forest’s protection and the flow of tourists.

Map of Sundarbans National Park

Zoom onto the Google Map of Sundarbans Nation Park to view details of the region:

Books about the Sundarbans

Planning a visit to Sundarbans National Park? You may find these books useful:

Interested in environmental issues? H.S. Sen has edited The Sundarbans: A Disaster-Prone Eco-Region:

The Rough Guide to India:

Accommodation in West Bengal

Find hotels near Sundarbans National Park and elsewhere in West Bangal via the Booking.com website:

Booking.com

Further information

The Sundarbans National Park website has information about lodges and visiting the park. The best time to visit Sundarbans National Park is widely regarded as October into March.

See the Incredible India website for ideas about things to do and see when visiting India.

Thanks for reading this post about Sundarbans National Park in West Bengal, India. You may also appreciate this post about Jodhpur in Rajasthan, India’s blue city.

Stuart Forster, the author of this post, is an award-winning travel journalist. He has travelled extensively in India. His work has been published in The Telegraph, The Independent and Rough Guides.

Photography illustrating this post is by Why Eye Photography.

If you enjoyed this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts on a monthly basis.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.

A version of this post was originally published on Go Eat Do on 22 September 2013.

Joydeep Das

February 15, 2021 at 05:55Hi,I am a regular visitor of Sunderbans.I own a houseboat MB Falcon over there carrying tourists & photographers.I am an amateur wildlife photo enthusiast too.

Go Eat Do

February 15, 2021 at 09:37I can imagine that travelling by boat opens up some tremendous photographic opportunities in the Sundarbans.