Stuart Forster visits Central America and reports on the experience of viewing remains of Maya houses at the Joya de Cerén UNESCO World Heritage Site in El Salvador.

Disclosure: Some of the links and banners below are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

“Like Pompeii in Italy, this place was buried in volcanic ash. It left the place intact,” explains Eduardo, my guide. With an outstretched arm and open palm, he gestures beyond my right shoulder towards the remains of the Maya village 600 metres away.

A cold finger of sweat rolls down the back of my neck, cooled by the air-conditioning of the site’s museum. Around us, artefacts are displayed in glass cases. Wall displays contextualise the existence of long-hidden buildings discovered in 1976. They count among the most significant of El Salvador’s historical sites.

Joya de Cerén in El Salvador

A bulldozer clearing earth, in preparation for a construction project, cut into the ground and revealed pottery plus a wattle-and-daub wall. An archaeologist identified them as dating from the Maya civilisation’s Late Classic period — between approximately 600 and 900AD.

The buildings were under four to six metres of ash spewed from the Loma Caldera, part of the San Salvador Volcano, during an eruption around the year 600. The carbon dating of thatched roofing from Joya de Cerén has resulted in the year of the eruption being dated within 10 to 15 years on either side of the beginning of the seventh century.

Payson Sheets, an American archaeologist and Maya specialist, played a key role in the subsequent dig.

“We found the missing link between the upper and lower classes,” says Eduardo of the significance of the archaeological site, one of the top places to visit in El Salvador for culturally engaged travellers.

I hear how the Salvadorian Civil War, which rumbled on from 1979 until 1992, limited what could be done at the site. There was no fighting around Joya de Cerén but an army base was located around a kilometre-and-a-half away.

The Pompeii of the Americas

“We can identify the time, month and the approximate year of the eruption from what was found,” explains Eduardo with his characteristic enthusiasm.

“Dirty dishes were left because of the eruption, which happened in the evening. People were eating beans. Some of the pottery bears finger marks of people who died long ago,” he adds earnestly. “Corn found here means it’s possible to say that the eruption was in the last two weeks of August or the first week of September — around the time of the harvest.”

The site provides evidence that common people consumed chocolate more than 1,400 years ago. It was long thought that only the ruling dynasty consumed it. As we follow a path through the dense vegetation inside the gated archaeological zone, Eduardo points out a green pod hanging like a deflated rugby ball from a cacao tree. He explains that the seeds within the pod are the raw material from which chocolate is made.

Maya ruins in El Salvador

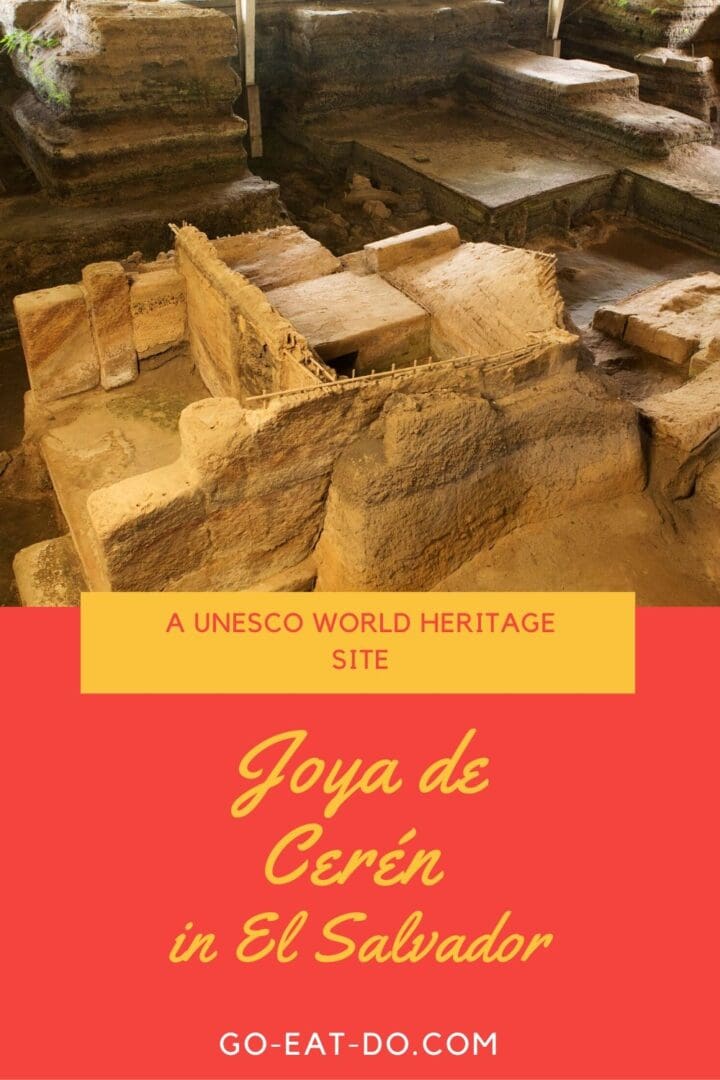

We are beneath a structure reminiscent of an aircraft hangar. A metallic roof arches over a pit whose sides have stratified earth. It contains the excavated remains of buildings that are regarded among the most significant Maya ruins found in El Salvador or elsewhere in Central America.

The roofing protects the ancient remains from bright sunshine as well as the rains that fall from mid-May to October. Today, a warm and sunny day, the shade ensures it’s cool enough to linger at the excavated site.

As we stare down at the exposed walls and doorways of buildings used by people long ago Eduardo explains that food was hung in pots to keep it safe. Likewise, medicines and obsidian knives were stored away from the ground, presumably to keep them out of the reach of children.

No human remains have been discovered at the site, indicating that people fled when they felt tremors prior to the eruption from the Loma Caldera.

Excavations have found skeletal remains of mice and ducks but no rats. It seems that the latter were introduced on European ships after 1492.

The significance of Joya de Cerén

Artefacts found at the site have helped archaeologists to develop an understanding of everyday rural life in Mesoamerica.

UNESCO designated Joya de Cerén a world heritage site in 1993. It remains the only one in El Salvador.

So far, 10 buildings have been excavated. Approximately 200 more remain buried in ash. Their bamboo wattle and daub construction proved flexible enough to survive the earth tremors of the volcanic eruption.

The houses had verandas, suitable for outdoor work. Their roofs were not connected to the walls, enabling air to circulate.

The site has revealed a shaman’s house. The curved, low entrance is believed to recreate a cave — a sacred place. It has a grilled wall reminiscent of an air brick or a church’s confessional.

To my surprise, the site has a sweat bath or sauna. Made from clay, the building had a domed roof. We see a recreation of the structure on leaving the archaeological site.

Joya de Cerén has proved a fascinating place to visit. I leave craving more knowledge about the Maya civilisation and, perhaps a touch more tenuously, a fix of chocolate.

Getting to Joya de Cerén

Planning on travelling to El Salvador and considering things to do? The Joya de Cerén archaeological site is a 40-minute drive northwest of the heart of San Salvador, El Salvador’s capital city. That makes it ideal for day trips from San Salvador:

Google map showing the location of Joya de Cerén in El Salvador.

Entry to the Joya de Cerén archaeological park costs US$3.

Accommodation in El Salvador

Search for places to stay in El Salvador on Booking.com:

Further information

Find out more about Joya de Cerén and other attractions in Central America on the Visit Centro America website.

For ideas about things to do and see across the country see the El Salvador Travel site.

Looking for a guide in El Salvador? Contact Eduardo Arriaza Siliezar via his Instagram account or Whatsapp (+ 50 3757 25394).

Enjoy this article about visiting the Joya de Cerén UNESCO World Heritage Site in El Salvador? You may enjoy this post about smartphone photography in Central America.

If you enjoyed this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts on a monthly basis.

To see more from Go Eat Do, please consider liking and following the Go Eat Do Instagram and Facebook pages.