Stuart Forster heads to Shakat Tun Wilderness Camp, Kwäday Dän Kenji and Haa Shagóon Hídi for insights into the heritage of First Nations in Yukon, Canada.

Disclosure: Some of the links below and banners are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

It’s mid-August and swirling wind has already delivered autumn’s first dusting of snow to inhospitable peaks on the far side of Kluane Lake. Heavy droplets of cold rain begin splattering down and James Allen, a former chief of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, suggests we shelter under the jutting roof of one of the backwoods-style log cabins that provide accommodation for guests staying at Shakat Tun Wilderness Camp.

As if to emphasise the remoteness of this location and the Yukon’s sparse human population, a black bear paused by the Alaska Highway to stare at our SUV as we motored past her during the 37-mile drive from Haines Junction. This Canadian territory is almost twice the size of the United Kingdom yet it’s home to less than 43,000 people. The small British towns of Coatbridge, Jarrow and Merthyr Tydfil each have more residents.

First Nations in Yukon

Fourteen First Nations have their traditional territories in the Yukon. Hunting and gathering are key elements of the semi-nomadic peoples’ long-established ways of living. Yet much has changed since the time of the Klondike Gold Rush, which began in 1896 and continued until 1899, when settlers of European origin poured into this part of North America seeking to make their fortunes.

Travelling on the Alaska Highway

Notably, World War Two saw the construction of the Alaska Highway through the Yukon, enabling materiel and troops to be transported. Still a key transport artery, that road skirts the distant shore of Kluane Lake and is today a common route on summer road trips, with motorhomes – RVs, or recreational vehicles, as they are known here – a popular way of combining transport and accommodation.

I’m keen to learn more about the region’s First Nations‘ heritage during my own road trip; one that yesterday saw me step out from behind the steering wheel for an hour-long sightseeing flight over Kluane National Park and Reserve. Spanning an area larger than Wales, Kluane is the home to Mount Logan, Canada’s tallest mountain, and the world’s largest non-polar icefield. Frozen lakes looking much like vast, flawless sapphires and deep crevasses reminiscent of caves prompted muttered wows as the light aircraft I gazed from flew above the St Elias icefield. We banked and turned above a plateau decked by pristine snow after viewing the peak of Mount Logan being warmed by the afternoon sun.

Shakat Tun Wilderness Camp

Today the conditions are different but here in the Yukon they say there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing. After the squall passes, James invites us to follow him into the yurt lodge of the wilderness camp whose name means ‘summer hunting trails’ in the Southern Tutchone language.

To my surprise, when I ask James how many people talk the language that his parents spoke at home he shrugs and answers “maybe 20”. In what is now regarded as a shameful episode in modern Canadian history, indigenous youngsters were forced to speak English while attending residential schools. Away from their families, many became detached from the culture of their ancestors. In addition to providing travellers with insights into First Nations’ life, camps such as this one help preserve and share traditional ways of living.

“They wanted to assimilate native people to the white man’s way of life. They outlawed potlatches [community ceremonies], the language – anything that made you First Nations or a native person was outlawed. And they tried to make you become like them. I’m glad a lot of people, like my family, grew up traditionally. A lot of younger people go to university but what’s lacking, I guess, is the traditional knowledge,” says James.

Handicraft sessions in the Yukon

Here at Shakat Tun he shares that, demonstrating the likes of traditional hunting methods and how to craft tools from natural materials such as bones and antlers. Barbara, James’ wife, invites guests to participate in handicraft sessions. During a group session in which me and other guests stitch leather purses, I notice that the shoulders of the former chief’s tasselled waistcoat are decorated by beadwork flowers. Even for hands far more skilled than mine, the floral motifs must have taken many hours to create.

That must pass time on cold nights. Whitehorse, the Yukon’s territorial capital, lies on a more northerly latitude than the Scandinavian cities of Stockholm and Oslo. The Yukon’s winters are traditionally harsh but the impact of global warming is increasingly evident.

“When I’m travelling, I don’t trust the ice anymore. You don’t know if the ice is thick enough to hold a Ski-Doo. It affects just about everything on the land,” he says before explaining that the winter of 2018-19 was the first of his life in which he’d not set traps.

The Long Ago Peoples Place

That observation is echoed by Harold Johnson at Kwäday Dän Kenji – the Long Ago Peoples Place – in Champagne, 55 miles west of Whitehorse. “I don’t consider myself an elder but I’ve seen a temperature change of about 20°F in my lifetime. I remember when I was a child it was regularly -65°F [-53°C],” he recalls of winters. “Last winter it never hit -40°F. As humans, I think that’s our biggest concern,” he adds solemnly, noting that several invasive plant and animal species – including coyotes – have established themselves in the region within his lifetime.

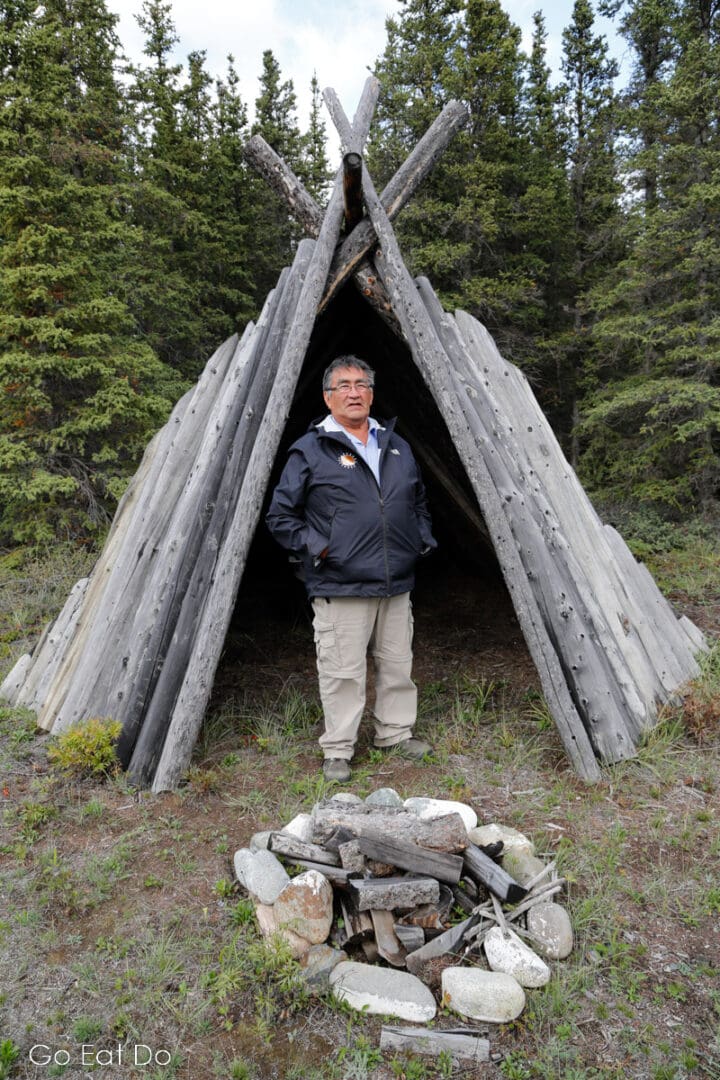

Harold opened the Long Ago Peoples Place in 1995 to share insights into the heritage of his people. “It’s about reconciliation to foster better relationships between all peoples,” he explains.

During the course of the morning, he shows me and other guests a variety of traps and shelters historically used by people of the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations to gather and preserve food. He explains that his people would move according to the season and the bounty offered by the land.

Bannock and tea

After inviting us to sit down for a cup of tea served with bannock, a type of scone-like pan-fried bread, and jam made from locally picked berries, Meta Williams takes us foraging.

“We go through the forest and take what we need…it’s like a medicine cabinet out there,” she enthuses. Meta talks to trees when harvesting, explaining why she’s picking berries or the likes of spruce tips, which can be rendered into an ointment for treating burns.

Carcross/Tagish First Nation

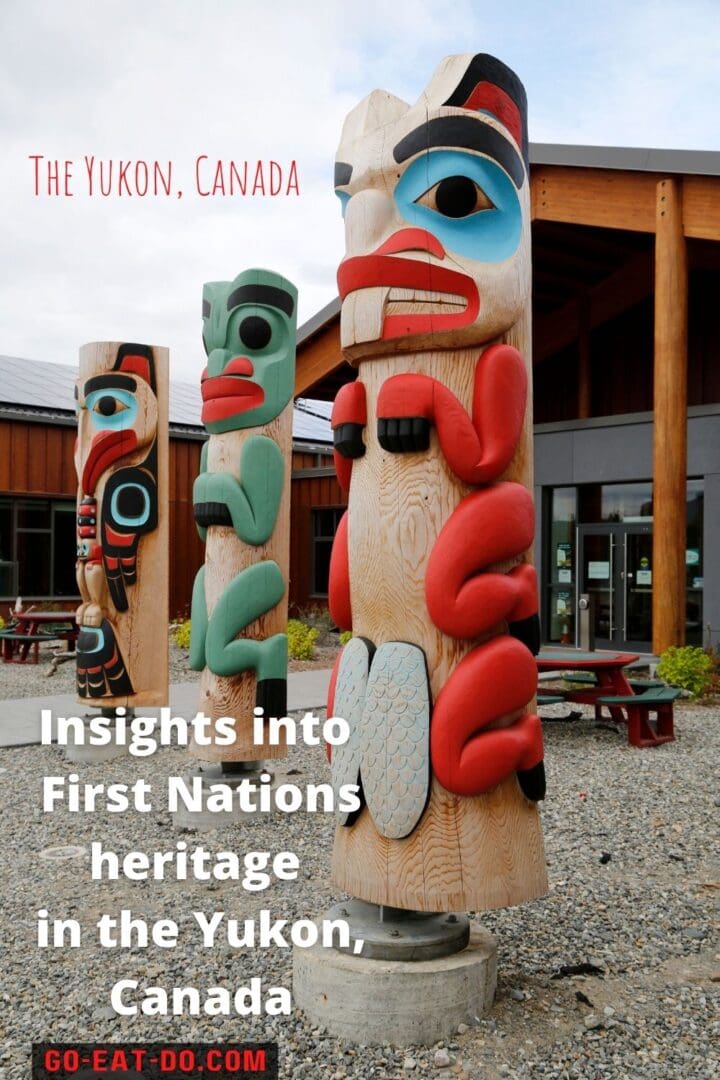

To understand more about the resurgent art of totem pole carving, I head south along the Klondike Highway towards Haa Shagóon Hídi – the cultural centre of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation. With the building in sight, I pause at the world’s smallest desert to tramp barefoot in the sand and snap a selfie, grinning next to the sign bearing the name of the Carcross Desert.

A series of totem poles stand outside of the building, whose name means ‘Our Ancestors House’ when translated into English. It’s there that I meet Keith Wolfe Smarch, who explains that he became a carver in the 1980s. Around then, people stepped up efforts to photograph details of totem poles in coastal areas to help ensure that the traditions were preserved.

Keith explains that the poles we see were carved from red cedar wood, which exudes a natural chemical that repels insects. Hollowed rather than solid poles tend to stand for longer and the colours with which they are decorated have symbolic meaning. Blue signifies wealth while white, made from burnt and crushed shells, means peace.

The Animal Mother foundation legend

Oral histories enabled First Nations’ peoples to share and retain traditions, knowledge and creation stories. “The Animal Mother built a hammock from the four mountain peaks around us,” explains Keith while standing in front of a totem pole with a grizzly bear at its base that depicts his take on the Animal Mother story.

“Right above Carcross, she created a hammock and then all of the animals as we know them today. Some she changed as they were born, and gave them instructions on where and how to live,” adds Keith, who explains that in some versions of the story the Animal Mother has two husbands. In others, she travels with her husband and brother-in-law.

Haa Shagóon Hídi

Haa Shagóon Hídi is built on a tongue of land at the western end of Nares Lake. Long ago animals forded the narrow stretch of water while migrating. Consequently, a settlement known as Caribou Crossing was established. Confusion over postal deliveries, caused by a place having a similar name in British Columbia, prompted Caribou Crossing to be renamed as Carcross back in 1904.

Standing in front of a totem pole, Keith explains that creating it with his son took 14 months. As many as 40 people were needed on either side to carry the pole from his nearby workshop, into which Keith invites me for a bowl of soup. On the way, I learn that wearing his traditional regalia, the carver danced during the raising ceremony, signifying that ownership of the totem pole was transferred to the community.

The insights I’ve gained into First Nations’ traditions have proven fascinating and fulfilling. From Whitehorse, an hour’s drive away, I’ll return home. Though that seems a world away, the underlying threats posed by changing weather patterns are as evident there as they are in this beautiful northern landscape.

Map of the Yukon

The map below shows some of the places where visitors can discover aspects of First Nations heritage in the Yukon, Canada:

Travel to the Yukon

Erik Nielsen Whitehorse International Airport is the main point of entry for air travellers arriving in the Yukon. Air Canada, Air North, Condor and WestJet fly to Whitehorse.

Cruise ships and ferries dock at the Port of Skagway in the southeast of Alaska. It is a four-hour drive from Skagway to Haines Junction.

Hotels in the Yukon

Mount Logan Eco-Lodge is a welcoming place to stay near Haines Junction.

Find and book accommodation in the Yukon, including hotels in Whitehorse and Haines Junction, via Booking.com:

Books about the Yukon

Keen to know more about the Yukon? You can buy the following books from Amazon by clicking on the links or cover photos:

Yukon information

See the Indigenous Yukon website for further information about places to visit and things to do to experience insights into the indigenous peoples and their heritage.

Looking to find out more about things to do in the Yukon? The Travel Yukon website has information about the territory and its attractions.

The Destination Canada website has information about places to visit in the Yukon and travel itineraries.

Further information

Stuart Forster, the author of this post, is an award-winning travel writer based in northeast England. He has written for Love Exploring, The Telegraph and Wanderlust. He was awarded the 2017 British Annual Canada Travel Award for Best Online Content.

Photos illustrating this post are by Why Eye Photography.

Thanks for visiting Go Eat Do and reading this post about aspects of the heritage of First Nations in Yukon, Canada.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.

If you enjoyed this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts on a monthly basis.