Stuart Forster reports on what to expect at the Western Approaches Museum in Liverpool, England, a secret bunker used as a command centre during World War Two’s Battle of the Atlantic.

Disclosure: Some of the links and banners below are affiliate links meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

It’s easy to stroll past the grey building at the corner of Rumford Street and Chapel Street in Liverpool. Derby House looks unremarkable. With a hint of Art Deco in its design, the five-storey façade is typical of many office buildings built across Britain during the 1930s.

For decades Derby House’s secret was forgotten. During World War Two it housed the Allied command for the Battle of the Atlantic. Once a top-secret underground bunker the building is now a war museum. The Western Approaches Museum is one of Liverpool’s top tourist attractions.

“This bunker was actually commissioned in 1938, so slightly before we went to war. We think it was when the building above was being constructed, there were Ministry of Defence (MoD) offices above, and there were quite a few places in the country that they put these bunkers… apparently, the blueprints went under the guise of it being an underground restaurant, so the builders didn’t know,” explains Carmel Davis, from the visitor team of the Western Approaches Museum, after we descend the stairs into the building’s basement.

Western Approaches Museum in Liverpool

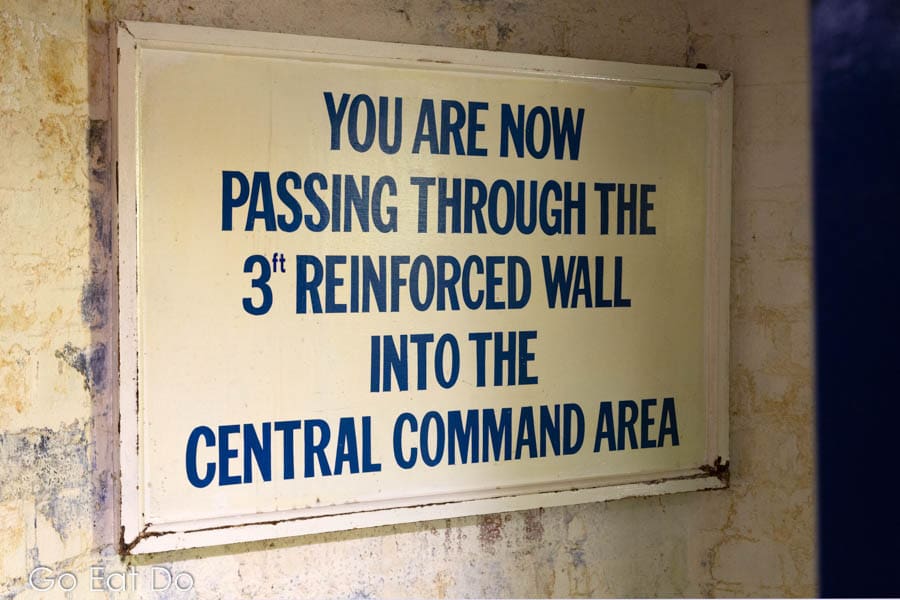

The bunker beneath Derby House was rediscovered, by chance, by construction workers building Rumford Street Car Park. The subterranean network of rooms once covered an area of about 55,000 square feet but approximately 20,000 of those have been lost. The reinforced concrete roof of the underground complex is seven feet thick and its grey walls have a width of three feet. Reputedly gas-proof and bomb-proof, the complex was nicknamed ‘the citadel’ and was guarded, inside and out, by Royal Marines.

“The Battle of the Atlantic was controlled from here. The Western Approaches was originally based in Plymouth but with the fall of France and the fact that the channel was so dangerous, that’s why it moved here to Liverpool in ’41,” says Carmel, who is wearing a navy blue costume and tie. It’s similar to wartime uniforms worn by members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS), whose personnel were nicknamed Wrens, because of the service’s acronym. The WRNS peaked at approximately 75,000 servicewomen in 1944. Some worked within the Western Approaches Command, alongside personnel from the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF), whose strength peaked at more than 180,000 in 1943.

Women at the Western Approaches

“The uniqueness of this building was the fact that it was both Royal Air Force (RAF) and Royal Navy. The RAF coastal command came under the control of the naval commander-in-chief, Sir Max Horton, and the personnel was predominantly young women, 16- and 17-year-old WAAFs and Wrens…the other personnel would have been older, more mature male officers — either retired and brought back for their expertise or nearing retirement. The girls were doing important work,” says Carmel.

“They had to be bright and good at maths. They had to make calculations of coordinates. It was a very busy and stressful job. They lived here for weeks at a time. We’ve got dormitory areas that have yet to be opened up to the public; going forward that’s what we’re hoping to do,” she adds as we enter the subtly lit operations room.

A vast map of the North Atlantic spans the back wall. Wooden desks, some stacked with papers, the map. Navy blue jackets are slung on the backs of two of the chairs as if their owners had stepped out of the room just moments ago.

Admiral Sir Martin Dunbar-Naismith was named the first Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches. Shortly after the Western Approaches HQ was transferred north to Liverpool that command passed to Admiral Sir Percy Noble. From November 1942 Admiral Sir Max Horton held the position until the command was closed on 15 August 1945. Horton developed strategies that are credited with playing a role in changing the course of World War Two, of which the Battle of the Atlantic was the longest campaign.

The Battle of the Atlantic

The United Kingdom needed to import provisions and materiel from across the Atlantic to survive and fight. A significant proportion of those imports were unloaded on Liverpool’s docks, making the city a strategic target for aerial bombardment. German submarines, known as U-boats, sank more than 2,600 Allied merchant ships, causing the deaths of more than 30,000 seamen. From the Western Approaches HQ, Horton implemented an aggressive hunt and destroy strategy that helped reduce Allied losses.

“The U-boat threat was Churchill’s biggest fear. At times we were three days away from starvation. Obviously, the country, at the time, didn’t realise that, but it was the thing that kept Churchill awake at night. So you really can’t stress the importance of this building enough, because of the work that was done here to turn the tide of the war,” says Carmel as I glance about the high-ceilinged ops room, imagining how it might have been with dozens of people moving about while orders were being barked and the positions of vessels were plotted on the map.

“We’ve got some things on the tables in the ops room, excerpts of personal experiences about what it was like to work here,” she adds

The Western Approaches Command

“400 personnel would have been working here at any one time, but it would have been a slightly bigger facility. We’ve been told that the overriding smell was of perspiration and cigarette smoke. Basically, you’ve got the RAF cabin, the naval cabin there, and the Commander-in-Chief’s office with a speaking tube down to here. He would be in constant contact with the officers who sat there. They passed information to the WAAFs and Wrens who would then go on ladders and plot the convoys of Allied ships, the U-boats and everything that was going on,” she explains, pointing towards the offices overlooking the ops room.

“We’ve been told that like the girls who went up the ladder, their knees were shaking. Not only was the ladder super-precarious, those coordinates had to be so perfectly exact, otherwise, it could have been the sinking of a ship and a lot of loss of lives,” adds Carmel, pointing towards two rickety-looking ladders that, in all honesty, I wouldn’t fancy climbing.

The aftermath of war

“Although it was hard work, stressful and it was very responsible, they enjoyed it because they felt that they were playing their part. When the war ended it was almost as though, ‘that’s it now; back to your normal life’. They said the camaraderie wasn’t there and the morale. You’d have to go and be a wife and a mother, I suppose. We know about the guys coming back and being a bit shell-shocked and needing to adjust. We don’t really think about the girls, the jobs that they were doing and then, all of a sudden, ‘oh, thanks, but we need the jobs for the boys now’,” says Carmel about the aftermath of the war.

It wasn’t just out on the North Atlantic that casualties were inflicted.

“There’s a plaque there, in memory of a WAAF who fell from the ladder and died. She’s the one fatality that we know of. We did have someone in when we first opened who said that they had a relative who worked here at the time and remembered it happening. Basically, they scooped her up and ran out. The next minute someone else was up the ladder because it had to go on,” she explains.

Liverpool War Museum

As we move between rooms Carmel explains that Liverpool was bombed heavily by the German air force, the Luftwaffe, during World War Two: “They bombed the centre of town and right the way down to Bootle, hitting the dock area. We believe that they didn’t know that this existed. They were just attacking the port and also the other side of the river, the shipyards at Birkenhead — Cammell Laird, which was building military ships… Churchill didn’t want the Germans to know how badly hit we were. They’d just say ‘a northern city’ had been hit.”

Photos of that wartime devastation are displayed in the Merseyside at War exhibition. The room’s design features recreations of shop facades that were in Liverpool at the time of World War Two. It tells local stories about people’s experiences of living in the heavily bombed city during a time of rationing.

Visitors to the Western Approaches Museum are given a pass to enter, like those that would have been shown to the marines posted at checkpoints around the building during wartime.

Winston Churchill in Liverpool

“We know that Churchill visited on a number of occasions, there’s evidence that he visited. This was meant to be the hotline to the War Rooms in Westminster. Whether that’s true or not, I don’t know,” says Carmel pointing to a snug-looking, soundproofed telephone box. “How he’d squeeze into that, I don’t know,” she jokes.

We pass the austere bunk room used by the Commander-in-Chief’s flag officer, Kate Halloran. “We only know a little bit about her. She played a big role at the time. The Commander-in-Chief was quite a stern guy and had a reputation for not being particularly approachable. They were all a little bit scared of him. They loved Percy Noble, he was a very affable chap, and they were a bit upset when he went but Horton was the man to do the job; Kate Halloran smoothed everything over,” explains Carmel about an aspect of the role played by one of the more senior women to serve at the Western Approaches.

In the Johnnie Walker Room, bearing the nickname of Captain Frederic John Walker, a hero of the Battle of the Atlantic, we watch a film featuring a snippet of people at work within the ops room that we just visited.

It seems remarkable that so few people know about that work or the existence of this historic site in central Liverpool.

Location of Liverpool’s Western Approaches Museum

The map below shows the location of the Western Approaches Museum in Liverpool:

Hotels in Liverpool

Planning a break in Liverpool and looking for accommodation? You can accommodation in Liverpool via Booking.com (£):

Booking.com

Further information

See the Western Approaches (1-3 Rumford Street, Liverpool; tel. 0151 2272008) website for information about the museum’s opening times and prices. Tours of the Western Approaches HQ take about 90 minutes. Tickets remain valid for a return within six months.

If you have artefacts or information relating to the wartime work undertaken in the Western Approaches, please get in touch with the museum, which is on the lookout for material for future exhibits.

For more about things to do and see in the city, take a look at the Visit Liverpool website.

Thank you for visiting Go Eat Do and reading this post about the Western Approaches Museum in Liverpool. I learnt about the Western Approaches Museum while on a Liverpool City Sights open-topped bus tour. If you’re planning a trip to Liverpool, you may also enjoy participating in a Beatles’ themed tour of the city.

Stuart Forster, the author of this post, is a history graduate and award-winning travel writer.

Illustrating photographs are by Why Eye Photography.

If you liked this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts. If you’d like to sponsor a post on Go Eat Do then please feel free to get in touch.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.

Anne

March 10, 2019 at 16:50I only heard of this place recently and it went straight on my things to do list though I wasn’t quite sure what exactly was there. Thanks for this post, I know more what to expect now and it seems even better than I thought it would be.

Stuart Forster

March 11, 2019 at 15:41I found it an enthralling place to poke around.