Stuart Forster visits Saalburg Roman Fort in Germany, discovering a historic site that once lay on the frontier of the Roman Empire.

Disclosure: Some of the links and banners below are affiliate links, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase.

Saalburg Roman Fort lies on the German Limes Route, about 30 minutes’ drive from Frankfurt-am-Main. The partially reconstructed fort is one of the key attractions on a scenic driving route with a Roman theme.

Visiting Saalburg Roman Fort

As I park my hire car within sight of Saalburg Roman Fort the authoritative voice of the GPS system, yet again, commands me to turn around. I take smug pleasure in turning off the engine having proven her wrong — I’ve reached my intended destination despite her best efforts to send me elsewhere.

Having twice zipped back and forth along Bundesstrasse 456, the highway that runs by the historic landmark, I’ve concluded that sometimes it’s easier to do things the old-fashioned way and simply follow directions provided by signposts than rely on technology.

Stepping out of the vehicle I look up at the sky. To my left it’s blue but over to the right there’s foreboding grey. Low clouds are rolling this way — not what I want if I’m going to take memorable photos of the only fully reconstructed fort along the 550-kilometre length of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, the erstwhile frontier of the Roman Empire in what is today Germany. The frontier forms the longest monument in Europe and is part of the Frontiers of the Roman Empire UNESCO World Heritage Site, along with Hadrian’s Wall, in northern England, and the Antonine Wall, in Scotland.

Frontiers of the Roman Empire

The German section of the frontier, between the Rhine and the Danube, was systematically guarded from the first century until around 260. At that point, Rome’s authority over this part of its empire collapsed.

In its heyday around 900 watchtowers would have provided elevated lookout points for guards to watch over the surrounding countryside. That meant being able to look from the Imperium Romanum into barbarian territory.

As many as 120 forts and fortlets garrisoned troops. 35,000 men were stationed along the Limes, a Latin term that is usually interpreted as signifying the militarised zone on the extremity of Roman territory.

During the second century, eight units of cavalry and 36 cohorts of infantry would have been based between Rheinbrohl and Regensburg.

Typical of military structures, the Roman frontier in Germany evolved over time. Timber watchtowers were replaced with stone in the middle of the second century. During the reign of the Emperor Hadrian, from 117 to 138, a palisade of halved oaks was added. Between 160 and 170 a wall and ditch were constructed.

The German Limes Route

Over the past few days I’ve been driving along the German Limes Route, which snakes for 700 kilometres between Bad Hönningen and Regensburg, following the line of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. The signposted route passes through 93 towns and cities in the Rhineland-Palatinate, Hessen, Baden-Wuerttemberg and Bavaria.

It’s one of more than 150 themed driving routes in Germany that guide tourists away from big cities towards locations that they may not otherwise have a reason to visit. The themes are diverse: castles, football, wine and even fairy tales provide inspiration.

The routes tend to follow scenic roads rather than autobahns. Following them can be a means of meandering through the countryside. In addition to the Roman aspects, being on the German Limes Route has enabled me to immerse myself in German culture and heritage, and prompted me to overnight in towns I would not otherwise have considered visiting.

At Ellwangen I drank local beer while listening to rock bands providing entertainment at the Stadtfest, the town’s free-to-visit summer festival. At Idstein I enjoyed strolling through the historic urban centre while photographing timber-framed buildings — the town also lies on the scenic German Timber-Frame Route, which zig-zags north-south.

Upper German-Rhaetian Limes

In woodland close to Rainau, a small town a little over 80 kilometres eastwards of Stuttgart, I saw one of the tallest remaining sections of the stone wall that was a key element of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes. Crunching across pine cones and bouncing over sun-dappled ground springy with fallen pine needles, I visited a remnant of the stonework accompanied by Dr Stefan Bender, an archaeologist working at Baden-Wuerttemberg’s Limes information centre in Aalen. “It was known as the Devil’s Wall,” said Dr Bender as we approached the stonework. “People thought in former centuries that the devil had constructed the wall.”

“We have traces of white plaster which was on the façade of the Limes. In former times people would see white plaster with red lines, reconstructing a sense of marble. It was important — it had a psychological impact and was a message to the Germans. It showed the powerful Mediterranean culture of the south,” explained Dr Bender as we stood in the forest.

The Romans, of course, would have cut down trees on either side of their empire’s frontier, clearing a belt around 80 metres wide through woodland. Even that, never mind the quarrying of stone and construction of the wall, would have been a time-consuming and labour-intensive task.

Watchtowers in Germany’s countryside

“In my opinion, it was not the border of the Romans but a controlling line to see who went in or out of the empire. They wanted to rule the world, so why should they have borders? It was only a technical line to control the traffic,” suggested Dr Bender as we stood in a reconstructed watchtower looking out over the countryside, like two auxiliaries performing frontier guard duty 18 centuries ago.

“It was a barrier but it has entrances. It looks like a border, nothing more,” he added, suggesting that the long-held view of the Limes as a border was a concept formed in the 19th century, an age of Nationalism.

The Kaiser’s interest in history

During that era, Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II developed a fascination for Roman history. In 1897 he announced that the restoration of the fort at Saalburg would be an imperial priority. State funding was supplemented by private donations. The reconstruction was led by Louis Jacobi over the next ten years. The focus, though, was on rebuilding the fort’s stone buildings. That meant traces of excavated timber were largely overlooked: barracks, stables and equipment rooms were not initially rebuilt.

Since 2004 additional buildings have been erected, reflecting the evolution in the understanding of Roman military architecture over the intervening period. A commander’s residence, known as the praetorium, and workshop (fabrica) are among the structures that have subsequently been added.

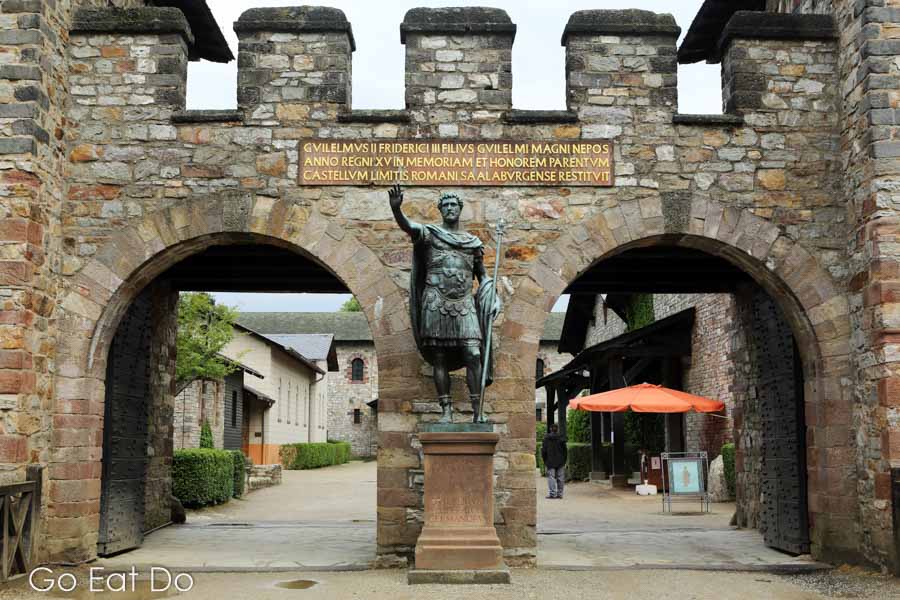

An inscription in Latin by Saalburg’s main gate, the porta praetoria, records the role of Kaiser Wilhelm II in instigating the reconstruction. A bronze statue of a much earlier emperor, Antonius Pius, stands between the arches of the gate. A sign informs me that I’ve arrived on a day during which reenactors will be performing.

Julius Caesar and gladiators

A man recites Cicero in Latin and, inside the great hall, musicians play instruments based on archaeological finds. “Et tu, Brute?” asks Julius Caesar with his dying breath, eliciting applause from those of us watching a group of actors performing the stabbing scene from Shakespeare’s play about the Roman emperor who was murdered on the Ides of March in 44BC.

Impressed, I watch as a gladiator brandishing a trident takes on a fearsome-looking, sword-wielding bearded barbarian. Between performances I mooch around the historic site, looking inside the likes of the principia, the garrison’s headquarters, and viewing a reconstruction of a triclinium, an arched dining room decorated with frescoes.

Roman fortress at Saalburg

Despite the reconstructions of more than a century ago, the site still has a handful of ruins, including a multi-room bathhouse. A low rail surrounds the stone outline of the bathhouse, in which soldiers would have cleansed themselves. They would have washed in the steam room before heading into a lukewarm room and then taking a dip in a cold bath. There’s also a building in which the outline of an underfloor heating system is immediately apparent.

After viewing those I head to Taberna, the onsite café, for lunch. I opt for a Roman-style platter, featuring olives, air-dried sausages and moretum, a type of herb-infused cheese that was eaten during ancient times. I sip from a glass of mulsum, a form of spiced wine infused with honey. The Romans did not know the joys of sipping a post-lunch espresso but I reason that is not going to stop me from ordering one.

Saalburg Circuit trail

Before departing I walk around the remainder of the archaeological park. The Saalburg Circuit trail runs for 2.4 kilometres and leads me past a temple dedicated to Mithras, reconstructions of civilian houses from the Roman era plus a column depicting Jupiter.

There are also the remains of earthworks dug in 1913 by 120 Prussian Army engineers. In what is regarded as an early example of experimental archaeology, the soldiers required 20 hours to construct an enclosure surrounded by a wall and wattle fence. While admiring the now overgrown and partially eroded ditch I realise that, a little over a year later, those same soldiers would probably have been digging trenches in the Great War.

I head back to my car with the intention of spending the night in nearby Bad Homburg. Shall I wrestle with the GPS again or simply follow the road signs?

Map of Saalburg Roman Fort

The Google map below shows the location of Saalburg Roman Fort in Germany. Zoom in or out of the map to see details:

Books about Germany and Roman history

Planning a trip to Germany? You can buy the following books via Amazon by clicking on the links or cover photos:

The Shortest History of Germany by James Hawes:

Roman Military Architecture on the Frontiers: Armies and Their Architecture in Late Antiquity:

Further information

Want to visit the fort? Find information about opening times and entry prices on the Saalburg Roman Fort website.

The Germany Travel website has more information about the German Limes Strasse.

A version of this feature has been published in Timeless Travels magazine.

Thank you for visiting Go Eat Do and reading this post about Saalburg Roman Fort in Germany. Please take a look at this post about sauna culture in Germany.

Photographs illustrating this post are by Why Eye Photography, based in the northeast of England.

If you liked this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts. If you’d like to sponsor a post on Go Eat Do then please feel free to get in touch.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.