Stuart Forster reports from the Frans Hals and the Moderns art exhibition in Haarlem, the Netherlands.

Disclosure: Stuart Forster, the author of this article, was invited onto a curator’s tour of the ‘Frans Hals and the Moderns’ exhibition. The Frans Hals Museum did not review or approve this feature.

A major art exhibition, Frans Hals and the Moderns opened in the Dutch city of Haarlem on Saturday 13 October 2018.

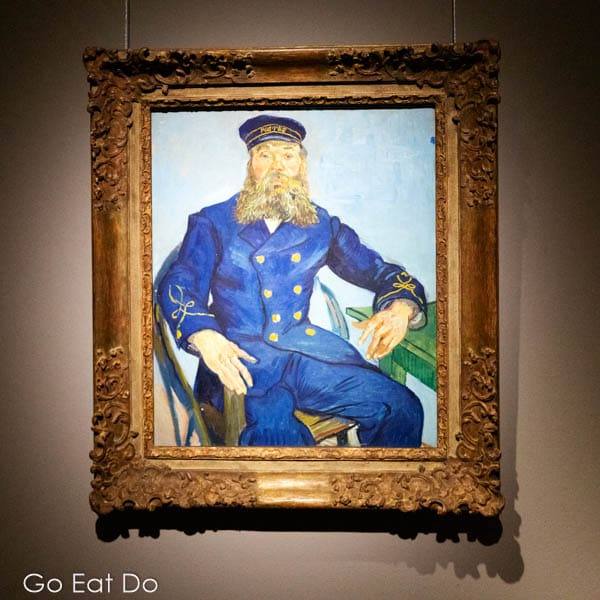

On display at the Frans Hals Museum, it features notable loan works such as Vincent van Gogh’s Postman Joseph Roulin, Édouard Manet’s Corner of a Café-Concert and John Singer Sargent’s Constance Wynne-Roberts, Mrs Ernest Hills of Redleaf (died 1932) in addition to works but the master after whom the building is named.

“Frans Hals posthumously became a teacher for a whole new generation,” said Ann Demeester, the Director of the Frans Hals Museum, while introducing the exhibition. “Associated with a wild lifestyle, Hals and his work became marginalised in the 18th century,” explained Demeester.

Shortly after the death of Hals, in 1666, his work became largely forgotten. Though the artist is now regarded as one of the masters of the Dutch Golden Age it was not until after the mid-1860s that his work was rediscovered.

Celebrating the Dutch Golden Age

Like many of creative souls of the Dutch Golden Age, Hals was born in Flanders during the late sixteenth century. Antwerp, his family’s home city, was under Spanish control while Holland and the northern provinces of the Netherlands struggled for independence.

Consequently, many people migrated from the south to the north. Their economic and intellectual capital are regarded as foundation stones of the Dutch Golden Age.

Next year marks the 350th anniversary of the death of Rembrandt van Rijn, another of the masters whose oil paintings depict characters from that era. In commemoration, museums and galleries in cities across Holland will be holding exhibitions relating to the theme of the Dutch Golden Age in 2019.

Frans Hals and the Moderns is the first major exhibition with that theme to open. It will continue into the New Year.

The Frans Hals Museum

The Frans Hals Museum spans two locations in Haarlem. One is termed the Hof (meaning ‘court’) and the other is termed the Hal (meaning ‘hall’).

The Hal is in a seventeenth-century market hall designed by the celebrated architect Lieven de Key, whose stone buildings typify the grand facades of the Dutch Golden Age. It stands on Haarlem’s main market square, the Grote Markt, just a few paces from the entrance to the Saint Bavo Church, in which Frans Hals is buried.

The Hof, the location of the Frans Hals and the Moderns exhibition is a five-minute walk from the cobbled marketplace. The museum occupies a former almshouse and orphanage with a sizable courtyard. It opened as a museum in 1913. The current exhibition is the first to occupy all the galleries within the building.

Restoring Frans Hals’ reputation

In 1863 Thoré/Bürger paid a visit to the Stedelijk Museum, the art gallery within Haarlem’s town hall that was a forerunner of the Frans Hals Museum. The building looks onto the Grote Markt. In 1868 he wrote two articles about Hals for Gazette des Beaux-Arts, an influential French art publication.

The articles restored Hals’ reputation and resulted in a surge of interest in the artist’s works. As a consequence, artists from Europe and beyond began travelling to Haarlem to study Hals’ paintings.

The loose, swirling brush strokes for which Hals had long been dismissed inspired artists during the late-nineteenth century.

Van Gogh and Frans Hals

“Van Gogh was obsessed not so much by Rembrandt but by Hals. His works opened Van Gogh’s eyes to colour and a new bravura method,” asserted Demeester at the opening of the exhibition. She explained that in letters written by Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo, the artist enthused about how Hals used colour to shape his paintings and featured more than twenty colours of black.

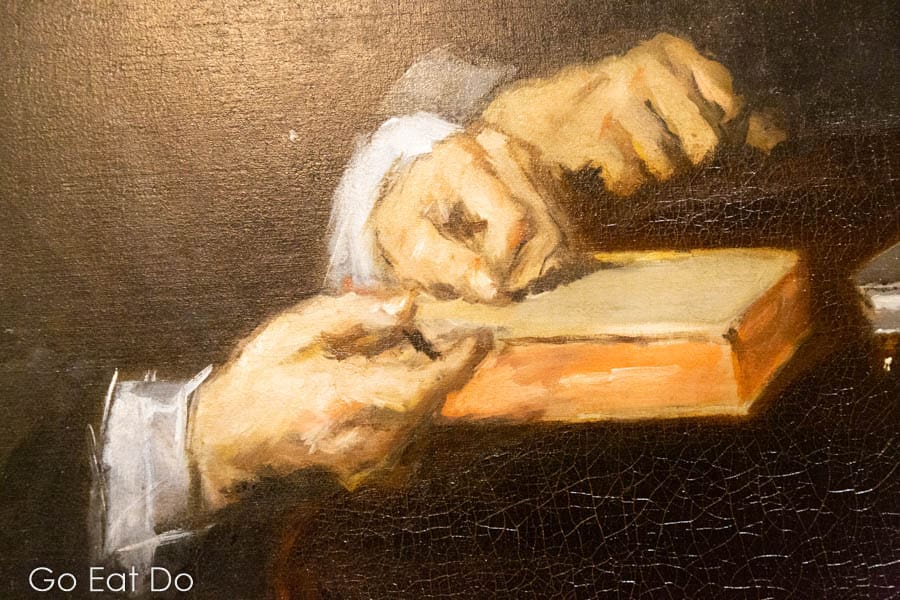

The hands-on Van Gogh’s portrait of Postman Joseph Roulin, on loan from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, are painted without significant detail. Spontaneity was also a feature of Hals’ works, ensuring that the focus was on the faces and expressions of his subjects.

“Nowadays our conservators would go crazy if people were to bring oil paintings into a gallery,” said Demeester while laughing. Yet in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, it became common practice for artists to visit Haarlem to study and make copies of Hals’ paintings.

Copies painted by artists who saw Hals as a figure of inspiration hang side-by-side with the original works in Frans Hals and the Moderns. They include Antoine Vollon’s The Banquet of the Officers of the St George Militia Company in 1616.

The faces of the sitters in Hals’ group portrait Regentesses of the Old Men’s Alms House exhibit strokes of yellow, white and red paint. He captured the spirit of the moment, working quickly, a style that contrasted with the more ponderous approach of his contemporaries. This was another reason why he appealed to artists active from the latter decades of the nineteenth century.

Curator’s eggs of wisdom

“We look at Hals through nineteenth-century artists. They are the eyewitnesses that follow us as we go through the exhibition,” said Marrigye Rikken, the museum’s Head of Collections and curator of the present exhibition.

“Hals was an idol for nineteenth-century painters,” she commented.

“Max Liebermann made more than 30 copies of Hals’ works, of which ten are extant. He did not copy any other artist,” said Rikken.

The admiration of Impressionists and Post-Impressionists for Hals often “can be seen in the composition, in the poses of sitters,” she added.

In 1910 the American artist Robert Henri took a studio above what is now Café Brinkmann, overlooking the Grote Markt. His work The Laughing Boy, on loan from Alabama’s Birmingham Museum of Art, bears similarities to Hals’ Laughing Boy, which is on loan from the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

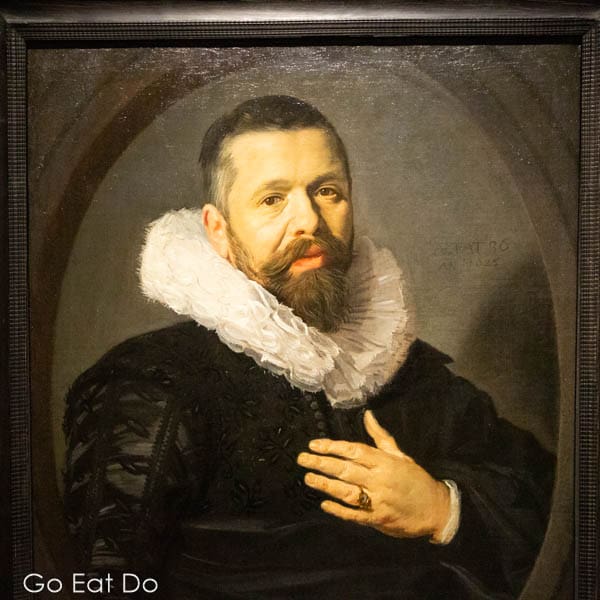

Ruff days for artists

Several artists active in the nineteenth century, including William Merritt Chase and Frank Duveneck, were inspired to paint sitters wearing ruffs around their necks.

Ruffs were worn primarily by wealthy members of society during the Dutch Golden Age. Yet unlike many of his contemporaries, Hals would also paint common people.

This prompted Gustave Courbet, the French painter who was an influential member of the Realism movement, to interpret Hals as an emancipatory social activist. Hals’ painting Malle Babbe, depicting a psychologically disturbed woman who is drinking from a pewter vessel, was one work that led him to this assumption, which Rikken suggests was reading too much from the paintings.

The final gallery of the museum explores how nineteenth-century photographers drew influence from Hals in their compositions.

Seeing the juxtaposition of artworks from more than two centuries apart is an effective and thought-provoking way of exploring the influence of Frans Hals on later generations of artists. Frans Hals and the Moderns continues until 24th February 2019.

Further information

For more information on the exhibition, see the Frans Hals Museum website. Adult entry to Frans Hals and the Moderns costs €23 (about £20). Combination tickets for visits to the Frans Hals Museum and the Teylers Museum, which hosts the exhibition Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo’s Original Drawings until 6 January 2019.

For ideas about things to see and do in the city, take a look at the Haarlem website. The Holland website also has information about the city.

Stuart Forster, the author of this post, was named Journalist of the Year at the Holland Press Awards of 2015 and 2016. He is available for commissions about the Netherlands and can be contacted via this website.

The photographs illustrating this post are by Why Eye Photography.

If you enjoyed this post why not sign up for the free Go Eat Do newsletter? It’s a hassle-free way of getting links to posts on a monthly basis.

‘Like’ the Go Eat Do Facebook page to see more photos and content.